Why Just Transitions Must Begin with Place: Insights from a Field Visit to the Langa Township

Written by: Dr Rihab Khalid, Loughborough University

As part of the JustGESI Annual Meeting in Cape Town, South Africa, our team had the opportunity to visit Langa Township — the city’s oldest planned Black township and a landmark of South Africa’s spatial history. The visit formed an important part of our collective reflection on what equitable, and socially inclusive energy transitions mean in contexts shaped by deep historical inequalities.

Langa’s layered history embodies many of the challenges that JustGESI seeks to address. It reminds us that questions of justice in energy and infrastructure are inseparable from questions of space, memory, and care. Visiting Langa allowed us to see first-hand how the legacies of apartheid urbanism continue to shape access to housing, services, and energy today, and why inclusive transitions must begin with these lived histories of exclusion.

1. Overview of the Township

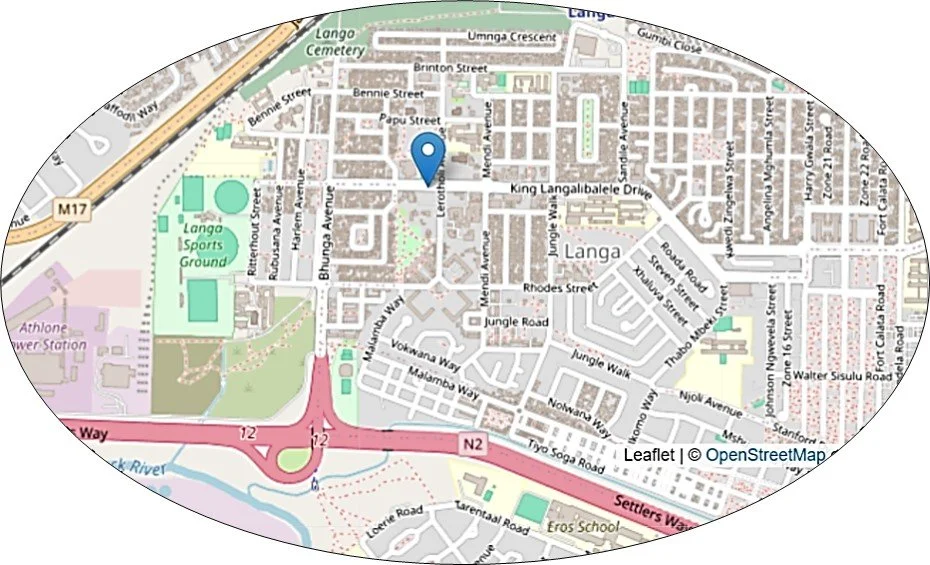

Langa Township, located on the Cape Flats approximately 11 km south-east of central Cape Town, is recognised as the city’s oldest planned Black township. Its name, Langa (meaning “sun” in isiXhosa), also honours Langalibalele, a Hlubi chief and rainmaker imprisoned at the Cape in 1873.

Formally established in 1927 under the Native (Urban Areas) Act of 1923, Langa was designed as a controlled urban settlement for Black labourers, reflecting the broader logic of racialised urban planning that later became the hallmark of apartheid. Today, the Langa Township and accompanying museum preserves this history, serving both as a site of remembrance for the violence of forced removals and as a living community space that offers a place of reflection on the persistence of spatial inequality.

Figures 1 and 2: Langa Township and its location in Cape Town. (Source: SAHO)

2. Historical Context and Museum Exhibits

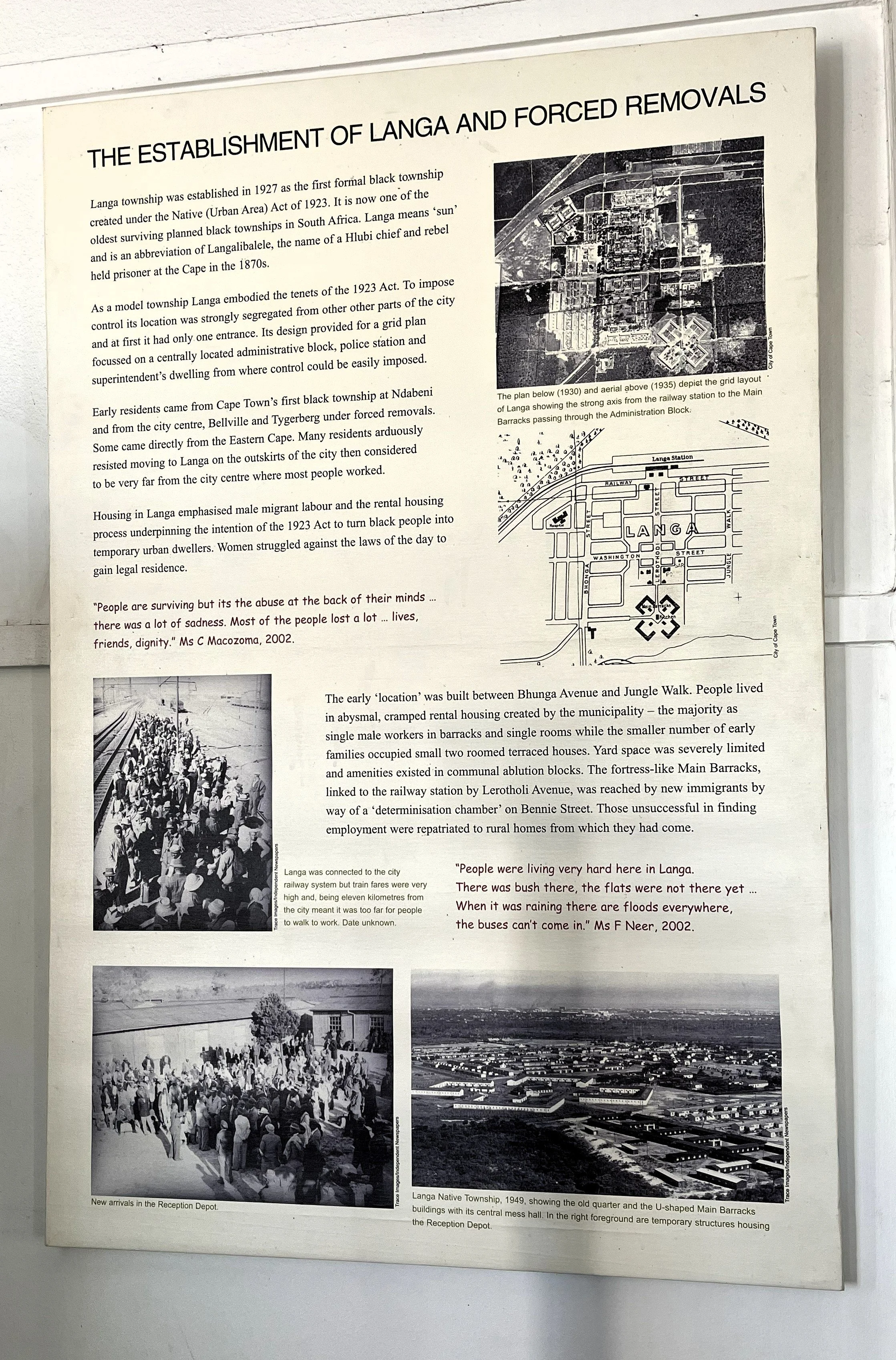

The museum exhibit showcased how the township was conceived to enforce racial segregation and regulate Black labour mobility. Its grid-like plan centred on a police station, superintendent’s residence and administrative offices- physical manifestations of surveillance and control.

During the field visit, we learned that Langa was initially reserved for men only, conceived as a dormitory for migrant labourers supplying cheap labour to the white economy. The guide explained: “Only men should come to the cities like migrant labour; they were not allowed to bring families.” Hostels and barracks were built “like concentration camps”, providing little more than beds in cramped dormitories. Workers “had no rights — just work and come back.”

Women and children were left in rural villages, often without economic or reproductive support, which, according to the guide, created “trauma passed down from generations.” The museum corroborates this, describing early Langa as a male-only compound where families were later admitted under strict supervision. Residents relocated from Ndabeni, Bellville, and Tygerberg resisted these removals, seeing Langa’s remote location as social and economic exclusion.

“People are surviving but it is the abuse at the back of their minds … there was a lot of sadness. Most of the people lost a lot — lives, friends, dignity.”

As the guide remarked, “apartheid on the ground started way before the 1940s — white people controlled the economy even though the Black population was the majority.”

Figures 3 and 4: Photographs and information boards on the history of the Langa township and its role in the struggle for liberation (Photos by Rihab Khalid)

The museum’s Dompas Reference Book exhibit reveals how documentation became a tool of subjugation. The dompas- literally “dumb pass”- was an internal passport required of all Black South Africans in urban areas. During our visit, we learned that this bureaucratic instrument was both physical and psychological control. The guide described it as a system to “legalise movement around the city” while ensuring confinement: anyone found outside authorised zones risked arrest. Many were detained or fined- “thirty to forty days in prison or pay ninety rand”, she noted.

The guide also highlighted symbolic domination: “Dom pass meant naming Black people with English names.” Newly arrived workers were “washed when they came — a process called dipping — before they could apply for the dom pass.”. These humiliations stripped identity and autonomy, illustrating how apartheid’s control extended into language and the body.

Figures 5 and 6: The Dompas (Photos by Rihab Khalid)

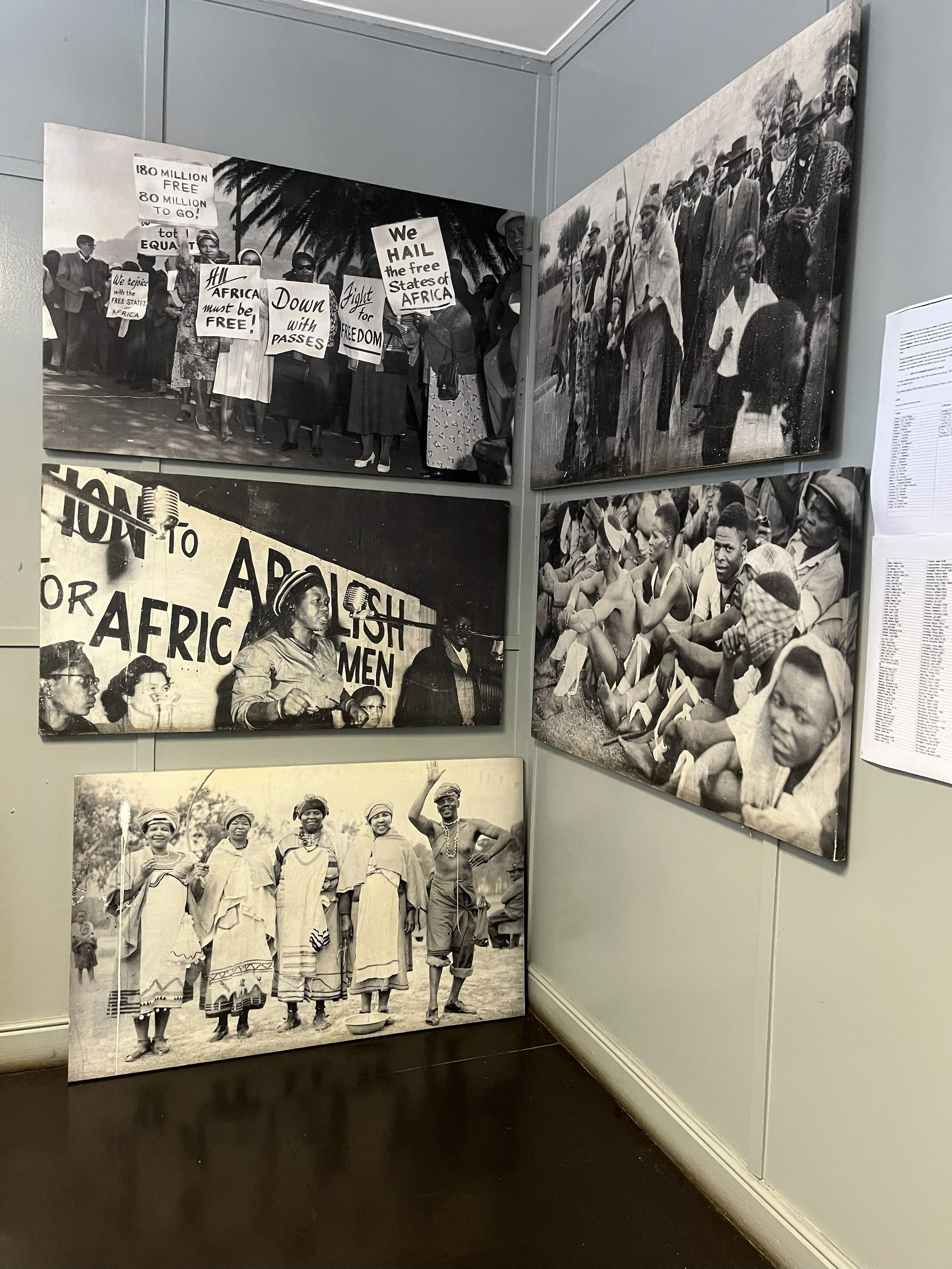

Struggles against forced removal and resistance to control remained a central part of the township. Local struggles continued from the 1930s, centred on living conditions, rentals, council policies and African representation. A critical turning point was the Women’s Anti-Pass Campaign in 1955 when thousands of women, organised by the ANC Women’s League, marched nationwide to oppose the extension of pass laws to women.

“Women took to the streets … to protest against the 1952 amendments of the Native Urban Areas Act requiring women to carry passes. ”

Black-and-white photographs depict women holding placards reading “With Passes We Are Slaves.”

During the field visit, the guide explained that these protests drew strength from women’s lived experiences of forced separation and economic dependency: “Their struggle was not only political; it was personal — about family, dignity and place.”. The campaign signalled the emergence of a distinctly feminist resistance within the broader liberation movement.

Langa’s role in the national liberation struggle is vividly portrayed in the museum’s exhibits. The Langa Marches of March 1960 were pivotal. Following the Sharpeville massacre, thousands joined a PAC-led anti-pass protest from Langa and Nyanga into Cape Town’s city centre.

“On 21 March 1960 Langa erupted … Police fired tear gas and live rounds. At least three people were killed … On 30 March a crowd of 30,000 streamed into the city … their leader Philip Kgosana was detained. ”

“The first people were in Cape Town and the last were still in Langa … The answer was the bullet.”

— Ms P. Fuku, 2002 (Museum Display Board)

Our guide described this as the moment “Langa became a political birthplace,” adding: “It started to cost white people, that’s when sanctions and international pressure began.”

The 1976 Student Uprising, inspired by events in Soweto, was another defining episode. The museum details how students in Langa and neighbouring townships boycotted classes in protest against compulsory Afrikaans instruction:

“On 11 August 1976 students held meetings … marched singing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika … police responded with bullets. Xolile Musi, a Langa High School student, was shot dead.”

“I could hear children singing so nice … the way they sang it was so beautiful I cried.”

Our guide elaborated that Afrikaans was deliberately imposed to reinforce intellectual subordination: “The government said Black people didn’t have the mental capacity for higher learning — they would be our labourers.” Photographs of young protesters and bullet-scarred walls convey the intensity of that resistance. The 1976 uprising remains a defining memory of collective courage in the face of systemic oppression.

3. Walking around the Langa Township and its contemporary state

Walking through Langa today reveals a landscape where the architecture of control and the aspirations of resilience coexist. The streets are lined with hostels from the 1920s, post-apartheid brick homes, and corrugated-metal structures converted into dwellings. The guide described three distinct standards of living: lower, middle and upper tiers, that continue to mirror social stratification.

Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10: Various views from the low-income housing in Langa Township (Photos by Rihab Khalid)

At the lower end, many households inhabit temporary shelters or shipping containers, sometimes for over fifteen years. In contrast to the precarious temporary shelters of the poor, middle-income families occupy modest two-storey homes with shared courtyards, while professionals and small-business owners live in newer detached houses. Every household now has an individual electricity meter, and power is used for cooking, lighting and domestic appliances — refrigerators, kettles, washing machines, televisions and, increasingly, air fryers.

Figures 11 and 12: Middle-income housing in Langa Township (Photos by Rihab Khalid)

Figures 12 and 13: Affluent housing in Langa Township (Photos by Rihab Khalid)

As the guide observed with humour, “After the World Cup, everyone wanted satellite dishes — men wanted to watch football. Now women use their own incomes to buy air fryers.” This comment, both casual and insightful, captured subtle gender shifts in consumption and autonomy: women’s independent income is reshaping domestic energy use and notions of convenience.

The township economy also reflects ingenuity. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, young entrepreneurs created WhatsApp-based delivery and errand services to help residents procure groceries or pay bills. One such enterprise, “Cloudy Deliveries,” was described by the guide as “similar to Uber Eats but with social impact and profit.” As the founder of the service noted, most transactions remain cash-based (about 80%), with the remainder via mobile e-wallets, highlighting both digital adaptation and limited financial inclusion.

Despite visible progress, inequalities persist. The guide spoke candidly about politics and accountability: “Young people are more hopeful, but leadership needs change. There is no accountability.” She also reflected on the enduring emotional burden of apartheid: “White people still say get over it, but the trauma is passed down.” Her words, set against the daily rhythms of market stalls and schoolchildren, encapsulated the contradictions of post-apartheid South Africa where hope and hurt coexist. Even as the country celebrates its identity as a “rainbow nation,” Langa reminds us that spatial segregation remains entrenched. Yet among younger residents, there is more inter-class and inter-racial interaction through schools, sports, and digital networks, quiet gestures towards the inclusive future envisaged but not yet realised.

4. Some reflections through a JustGESI lens

The visit to Langa Township illuminated the material and affective continuities between apartheid-era spatial control and contemporary urban inequalities. Langa’s layered history, from male migrant compound to politically charged community, embodies the entwined dynamics of spatial injustice, gendered exclusion, and social resilience.

a) Spatial Design as Control

The Langa township’s geometry and zoning reveal how built form was used as a spatial technology of governance: a material means of enforcing racialised labour relations while rendering Black urban presence visible, countable, and controllable. A regimented grid, central police station, and barrack-style hostels, exemplifies infrastructural violence — the deliberate use of built form to regulate populations and reproduce hierarchy. Surveillance, enclosure, and distance from the urban core further served as tools of domination. Langa’s urban formation demonstrates how colonial and apartheid planning continues to shape the geography of opportunity in the city today.

b) Gendered Structures of Labour and Care

The history of Langa reveals the deeply gendered nature of apartheid urbanism. The initial prohibition on women’s residence in the township institutionalised a gendered division of mobility: men were incorporated as workers; women were excluded as dependents. This spatial separation fractured families and displaced care work to rural spaces, entrenching a gendered economy of absence and dependency.

Nevertheless, the 1955 Women’s Anti-Pass Campaign showcased how women reclaimed political visibility by contesting control over their own movement and identity — transforming domestic vulnerability into collective resistance. Both these instances in the apartheid’s history show the critical role of gender in the apartheid’s political economy and the focus on women’s bodies and mobility as governed through both absence and resistance.

c) Identity, Language and Power

The Dompas system offers a striking case of biopolitical governance: the regulation of bodies through documentation, naming, and surveillance. The pass book was both an administrative and epistemic instrument; it defined who counted as a legitimate urban subject. By compelling Black South Africans to carry identification inscribed with colonial names, fingerprints, and racial classifications, the state reduced identity to bureaucratic legibility. From a feminist perspective, this represents a struggle over epistemic justice and authority: whose names, bodies, and languages are recognised by the system.

d) Energy, Infrastructure and Aspiration

The diffusion of household electrification and appliances in Langa offers an instructive microcosm of energy justice. Although most homes now possess access, energy consumption remains unevenly distributed along lines of legality through metered connections, income, gender, and housing quality- all means for configuring infrastructural citizenship. Nevertheless, the ability to use electricity for convenience, such as through owning an air fryer, a washing machine, or a refrigerator, is not merely about efficiency; but plays out in everyday enactments of dignity, time, and care.

Feminist energy scholarship emphasises that transitions cannot be measured only through kilowatt-hours or grid coverage. They must also account for the relational dimensions of energy use — who performs energy labour, who controls expenditure, and who benefits from convenience. In Langa, women’s growing control over appliance ownership and household decision-making suggests small but meaningful shifts in everyday energy sovereignty.

Yet, the persistence of informal dwellings and inadequate infrastructure reveals the limits of technological inclusion without structural redress. As JustGESI highlights, achieving gender-responsive energy transitions requires confronting the intersection of material, social, and institutional inequities that shape access.

e) Continuity of Structural Inequalities

Langa remains emblematic of South Africa’s uneven transformation. Physical proximity to Cape Town contrasts sharply with economic distance; apartheid’s spatial logic persists beneath democratic rhetoric. Perhaps most profoundly, the museum’s testimonies and the guide’s reflections on “trauma passed down from generations” remind us that justice is not only distributive or procedural but affective and intergenerational. A feminist ethics of care approach emphasises that any just transition must recognise the emotional labour of remembering, mourning, and rebuilding.

In this sense, Langa is both archive and laboratory: a place where the residues of injustice meet the practices of care that sustain hope. Its museums, murals, and oral histories function as counter-archives- restoring dignity to those whose stories were excluded from official records. The ongoing work of community guides, educators, and youth entrepreneurs embodies situated knowledge — knowledge that emerges from lived experience and care for place.

Dr Rihab Khalid is a Research Associate at Loughborough University.